The Guerguerat Crisis in Western Sahara

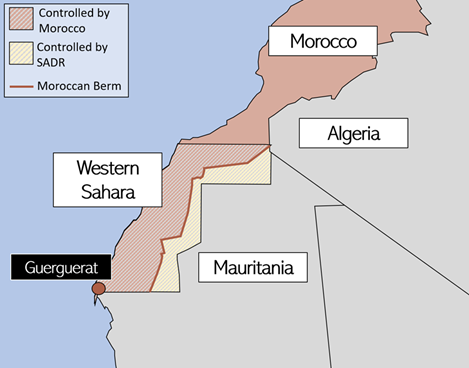

Western Sahara is an area in northern Africa, bordering the Atlantic Ocean, with a population of 600.000 people. The area is disputed; there are multiple parties who claim the territory as their own. Among these are the two neighboring countries, Morocco and Mauritania. Morocco in particular appears to be successful in this regard. It is estimated that 75-80% of the area is currently controlled by Morocco. The remaining part is not controlled by Mauritania, but by a third party: the Polisario Front. They proclaimed themselves to be the rightful rulers of the ‘Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic’ (SADR).

The two parts under different control are separated by a wall built by Morocco, called the Moroccan Berm. On the southern border of Western Sahara is a very small town – with only 28 inhabitants. The town has recently become the center of the battle for Western Sahara. This battle has therefore been given the name of the town: the Guerguerat Crisis. In order to understand this crisis properly, a historical background must first be provided.

This tripartite border reflects broader, unresolved processes of decolonization of which the conflict is a part, that goes all the way back to 1975. Between 1884 and 1975, the Western Sahara was a Spanish colony. When anticolonial uprisings across the region erupted and resulted in the withdrawal of Spain from the Spanish Sahara, Morocco and Mauritania gained administrative control over the territory. However, the rebel national liberation movement of the people of the Western Sahara, the Polisario Front, claimed their right of self-determination and established the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in 1976. With Morocco, Mauritania and the SADR making claims over the same territory, an armed struggle broke out and lasted from 1975 to 1991. Whereas Mauritania withdrew from the conflict after signing a peace treaty with the Polisario Front in 1979, a ceasefire between Morocco and the Sahwari people was not reached until 1991.

In October 2020, after years of ceasefire, violence resumed. Peaceful Sahrawi protesters blocked one of the few roads linking Morocco to sub-Saharan Africa, making it an economically crucial road. The Sahrawi people consider the road to be in violation of the ceasefire. The protests and blockades that therefore followed, were taking place near the town of Guerguerat.

A month later, on November 13, Morocco launched a military intervention to undo the blockade of protesters. The SADR responded to this with a request to the UN to intervene; the Moroccan army is said to have shot innocent civilians and with this the ceasefire was definitively violated. A day later, the SADR declared war on Morocco. Since then, there have been regular attacks and bombings around the Moroccan Berm, operated by both parties.

Algeria has been involved in Polisario Front from the beginning and is a great support, both ideologically and materially, by providing weapons. The dependence on this support is considered to be so extensive, that the assumption is made that every major decision of the Polisario has first been approved by Algerian leaders. As a result of this say and support, tensions between Algeria and Morocco continue to rise, especially now that the conflict has flared up again.

Internationally, there is no alignment in the recognized control of the area. There are some countries that regard Polisario Front as the rightful rulers of the area, among them Algeria and South Africa. Countries like Cuba and Venezuela talk about the ‘right to self-determination’ for the Sahrawi people. However, the United States has expressed its support for Morocco while President Trump was still in power. “The United States believes that an independent Sahrawi State is not a realistic option for resolving the conflict and that genuine autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty is the only feasible solution”. The US’ decision to support Morocco was part of a deal; Morocco had to agree to normalize relations with Israel. It is not expected that this pronounced support will be much determinative or influential.

The conflict is believed to continue today. The amount of journalistic research into the conflict is scarce; it therefore seems to be somewhat of a forgotten conflict. As a result, the number of deaths and refugees caused by the attacks and bombings is also unclear and hardly traceable. Figures that come out are usually from Polisario Front, which makes the reliability questionable.

One research institute that has addressed the Guerguerat Crisis and the wider conflict is the International Crisis Group. They prepared a report on ‘what should be done’.

Want to know more about this? Head to the resource bank via the link!